I recently had a discussion with a friend about the late, great writer Ernest Hemingway.

My friend was not particularly fond of Hemingway, but he admitted that he had only read a novel or two of his many years ago.

I

told him I’ve been a Hemingway aficionado since I was a teenager, and I

suggested several novels and short stories that he ought to read.

He

agreed to read them and reevaluate his view Hemingway.

I also sent my friend a link to my 2009 Crime Beat column on Hemingway and crime.

You can read the column below:

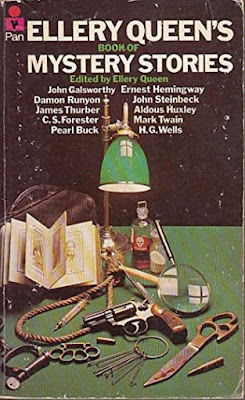

In Ellery Queen's Book of Mystery Stories, first published under the title The Literature of Crime, the crime stories presented in the collection are written by writers generally not recognized as crime, mystery or thriller writers.

Edited

by Ellery Queen, the pseudonym of the writing team of Frederic Dannay and James

Yaffe, as well as the name of their fictional detective character, the book

offers crime stories by Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson and

a dozen other writers.

Included

in the collection is a classic crime story by Ernest Hemingway called The

Killers. The short story is one of my favorites and it is perhaps

Hemingway’s best short story.

“Ernest Hemingway’s The Killers is one of the best known short

stories ever written and no volume dedicated to the literature of crime would

be complete without it,” the editors wrote in the introduction to the story.

“It is revealing nothing new about Hemingway to point out that essentially he

is preoccupied with doom - more specifically, with death. It has been explained

this way: ‘The I in Hemingway stories is the man that things are done to’ - and

the final thing that is done to him, as to all of us, is death. No story of

Hemingway illustrates this fundamental thesis more clearly than The Killers;

nor does any story of Hemingway’s illustrate more clearly why he is a legend in

his own lifetime. Here, in a few pages, is the justly famous Hemingway dialogue

- terse, clipped, the quintessence of realistic speech; here in a few pages,

are more than the foreshadowings of the great literary qualities to be found

in A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls.”"

He was wounded, returned home and he soon after

began covering crime and other subjects for The Toronto Star Weekly.

Hemingway credited his sparse, tough style of writing to his working for those

newspapers with their quick deadlines. Hemingway By-Line offers

a good collection of his newspaper and magazine pieces.

In his journalism, novels and short stories, Hemingway covered crime, love and war, hunting, fishing and bullfighting. In addition to The Killers, he wrote other short stories about crime, and he also wrote a good, tough crime novel called To Have and Have Not.

Humphrey Bogart portrayed Hemingway’s

tough-guy hero, Harry Morgan, in the film version of the novel. Bogart, of

course, also portrayed crime fiction’s iconic characters Philip Marlowe in

Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep and Sam Spade in Dashiell

Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon.

I

heard Elmore Leonard, one of our best contemporary crime writers, tell his

audience at the Philadelphia Free Library some months ago that Hemingway had

been a main influence on him (although he lamented that Hemingway lacked a

sense of humor). Many other crime writers, as well as writers of all stripes,

list Hemingway as a major influence.

I do

as well.

I devoured crime fiction and thrillers as a

teenager. I read Ian Fleming, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Ed McBain,

to name but a few. I also read literary fiction and Hemingway’s novels were a

favorite of mine.

After serving two years on an aircraft carrier

during the Vietnam War, I was stationed on a Navy tugboat at the U.S. nuclear

submarine base in Holy Loch, Scotland for two years. I was in my early 20s then

and I discovered Hemingway’s short stories, which I liked even better than his

novels.

I was pleased that some of them, like The Killers and The Battler were first-rate crime stories.

I traveled throughout the United Kingdom and Europe during those years. I visited Italy, France and Spain, which were the settings for many of Hemingway’s stories. While traveling across Europe I always carried what we called in the Navy an “AWOL” bag. In the small carry-all bag, among my toilet articles and a change or two of clothes, were several Penguin paperbacks books.

I loved those classic orange and white paperbacks and I still have many of them today. I bought and read Penguin’s Evelyn Waugh and Anthony Burgess novels, Mark Twain’s travel books, and many other classic books. I carried several of these paperbacks in my AWOL bag, along with Hemingway’s Penguin paperback short story collections, such as Men Without Women and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber. I read and reread these great stories.

Except for his tragic end, Hemingway led what

many writers consider the ideal writer’s life. He was successful, wealthy and

popular. He had the freedom to travel the world and hunt and fish, drink and

talk in bars, and cover what interested him.

Hemingway

covered wars, crime, sporting events and other happenings - and then returned

home to write about his adventures.

Hemingway truly loved the sea, and he lived near

the ocean in Key West, Florida and later in Cuba. I visited his home in Key

West some years back and I hope to one day visit his home in Cuba once the

communists are finally kicked off the island.

Hemingway died by his own hand in 1961, but he

lives on with his novels and stories. His family is releasing a newly edited

version of A Moveable Feast and there are two major film

productions in the works about his work and his life.

Hemingway is influencing yet a new generation of

writers and readers.

“Courage is grace under pressure,” Hemingway

once wrote.

He also wrote “A man can be destroyed but not

defeated."

HEMINGWAY AT WAR: ERNEST HEMINGWAY’S ADVENTURES AS A WORLD WAR

II CORRESPONDENT

By Terry Mort

Pegasus, $27.95, 304 pages

By Paul Davis, January 23, 2017.

As a Hemingway aficionado since my early teens, I’ve read all of

Ernest Hemingway’s novels, short stories, his letters and most of the

biographies written about him. I’ve also read collections of his journalism,

including the six articles he wrote as a war correspondent for Collier’s

magazine during World War II.

Since his suicide in 1961, there has been a steady stream of

books about Hemingway, whom many suggest may be the greatest and most

influential writer of the 20th century.

Of course, Hemingway has his detractors. Hemingway weaved his

real life through his fiction, thus creating the Hemingway persona and the

quintessential macho fictional Hemingway hero. This has made it easy for the

Hemingway haters to zero in on his personal life and disparage both his life

and his work by emphasizing his bragging, bullying and boozing. They have also

delighted in deflating his tough guy image by zeroing in on his time as a World

War II combat correspondent, branding him a coward, a liar and a fake

journalist.

Terry Mort, a writer who has written seven novels and

six nonfiction books, including “The Hemingway Patrols: Ernest Hemingway and

His Hunt for U-Boats,” offers an evenhanded look at Hemingway’s wartime role in

“Hemingway at War.”

“Hemingway had a talent for being at the center of important

events. Those events — and some of the people connected with them — are a large

part of this story. He was with the Allied landings on D-Day. He flew with the

RAF on at least one bombing mission. He flew with them during an attack of V-1

flying bombs. He operated with the French Resistance and the U.S. Office of

Strategic Services (OSS) as the Allies advanced to Paris.

And he was present and indeed active during the horrendous

carnage of the battle for the Hurtgenwald in Germany’s Siegfried Line. As such

he provides a useful lens to examine these events and also some of the people,

both the troops who fought and the civilian journalists who covered the

fighting,” Mr. Mort writes in his introduction. “Inevitably and understandably,

his exposure to people and events affected his journalism, and later his

fiction. This book attempts therefore to place him in the context of this

history and in so doing expand understanding of those events and their effect

on him, personally and professionally.”

I believe Mr. Mort largely succeeded in his goal.

At the outbreak of World War II, Hemingway was a world-famous

author basking in the critical and commercial success of his Spanish Civil War

novel, “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and living in Cuba with his third wife,

journalist Martha Gellhorn. She took off to cover the war for Collier’s, while

Hemingway remained in Cuba. With his fishing boat and friends he joined the

“Hooligan Navy,” the hundreds of volunteer yachtsmen, fisherman and civilian

pilots who took to the sea to provide intelligence to the Navy about Nazi

German U-boat submarines.

He later contacted Collier’s editors and arranged to become

their European frontline correspondent. Hemingway was nothing if not

competitive, so perhaps he was in competition with his wife, who thought he was

stealing her plum assignment.

Mr. Mort offers fine sketches of Hemingway’s fellow war

correspondents, A.J. Liebling, Ernie Pyle and others, as well as the military

people Hemingway accompanied throughout the war, such as OSS Col. David Bruce,

Private Archie “Red” Pelkey and Col. Charles “Buck” Lanham, who commanded

Hemingway’s favorite infantry outfit, the 4th Division’s 22nd Regiment.

In a letter Lanham wrote to his wife, he described Hemingway:

“He is probably the bravest man I have ever known, with an unquenchable lust

for battle and adventure.” So much for Hemingway being a coward. Lanham also

confirms that Hemingway did indeed fight alongside his troops while under heavy

attack.

But as a former naval officer during the Vietnam War, Mr. Mort

disputes some of Hemingway’s piece on the D-Day landings, noting that Hemingway

got some of the command terminology wrong and Hemingway’s descriptions of the

actions of the landing craft’s officer and coxswain ring false.

I was disappointed in Hemingway’s World War II novel, “Across

the River and Into the Trees,” thinking he ought to have written a war novel

more akin to his short story, “Black Ass at the Crossroads,” but Mr. Mort’s

book makes me think differently about the novel and I plan to reread it.

“Hemingway at War” is about much more than Hemingway, offering

what some might think of as padding, but I found Mr. Mort’s character sketches

and descriptions of momentous events that were the backdrop to the Hemingway

story to be interesting and informative.

This is a well-written and well-researched book that will

interest admirers of Hemingway, as well as those interested in the war in

Europe.

• Paul Davis is a writer who covers crime, espionage, terrorism and the military.

No comments:

Post a Comment